Subsidence monitoring in transboundary aquifers

An environmental drill behind the US/Mexico border wall as construction of the new section of wall begins at the Organ Pipe National Monument, August 23, 2019. Photo credit: AZCentral.com

An environmental drill behind the US/Mexico border wall as construction of the new section of wall begins at the Organ Pipe National Monument, August 23, 2019. Photo credit: AZCentral.comSome aquifers compact when groundwater is pumped out of water wells too quickly. Termed, “groundwater overdraft,” this overpumping causes the level of the ground to sink on the order of centimeters each year and is exemplified through this iconic photo illustrating the long-term implications of subsidence in California’s Central Valley.

In transboundary aquifers - regions where different diplomatic entities share groundwater - there is often a gap in the sharing of data across political boundaries, especially where those boundaries delimit geopolitical tension. A number of these aquifers are also the type of aquifer that will compact irreversibly due to groundwater overdraft.

Drawing from political scientific research into the governing characteristics of political institutions that successfully manage common pool resources, I sought to use methods in satellite radar remote sensing to fill a key characteristic of governing institutions for water sustainability: physically-based indicators of the condition of the shared resource across political boundaries.

In October 2019 I travelled to Valencia, Spain to give an oral presentation on monitoring subsidence in transboundary aquifers at the American Geophysical Union’s Chapman Conference on the Quest for Sustainability in Heavily Stressed Aquifers.

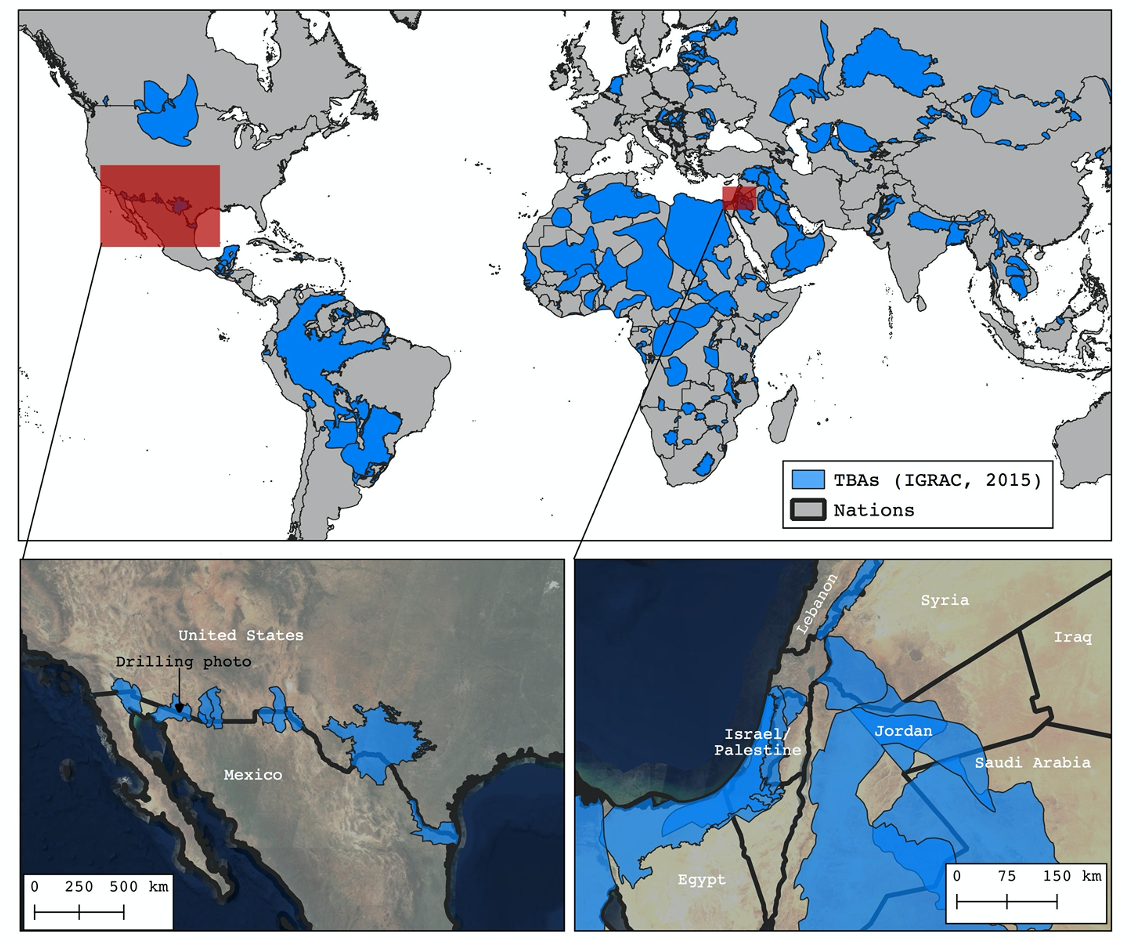

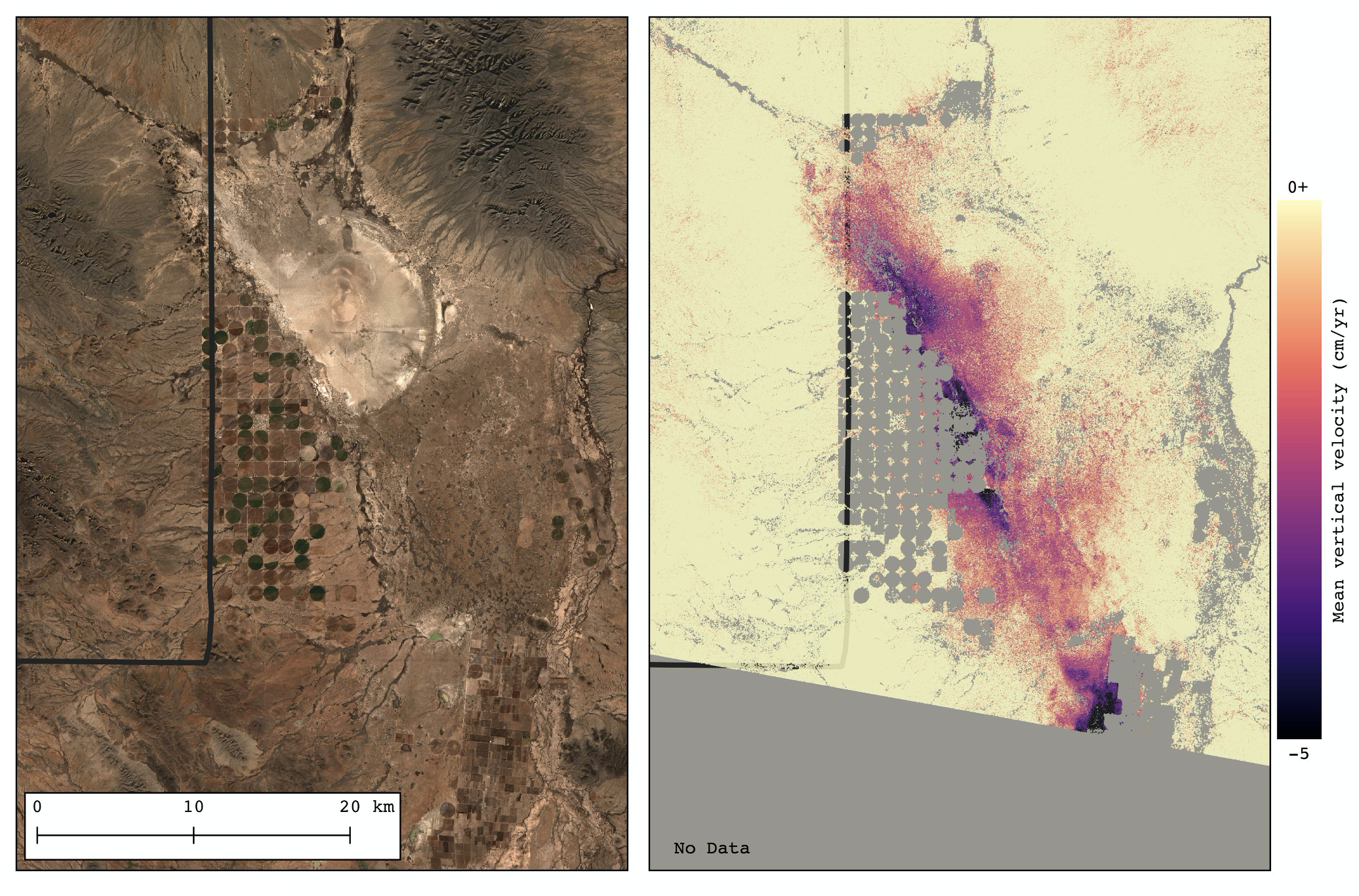

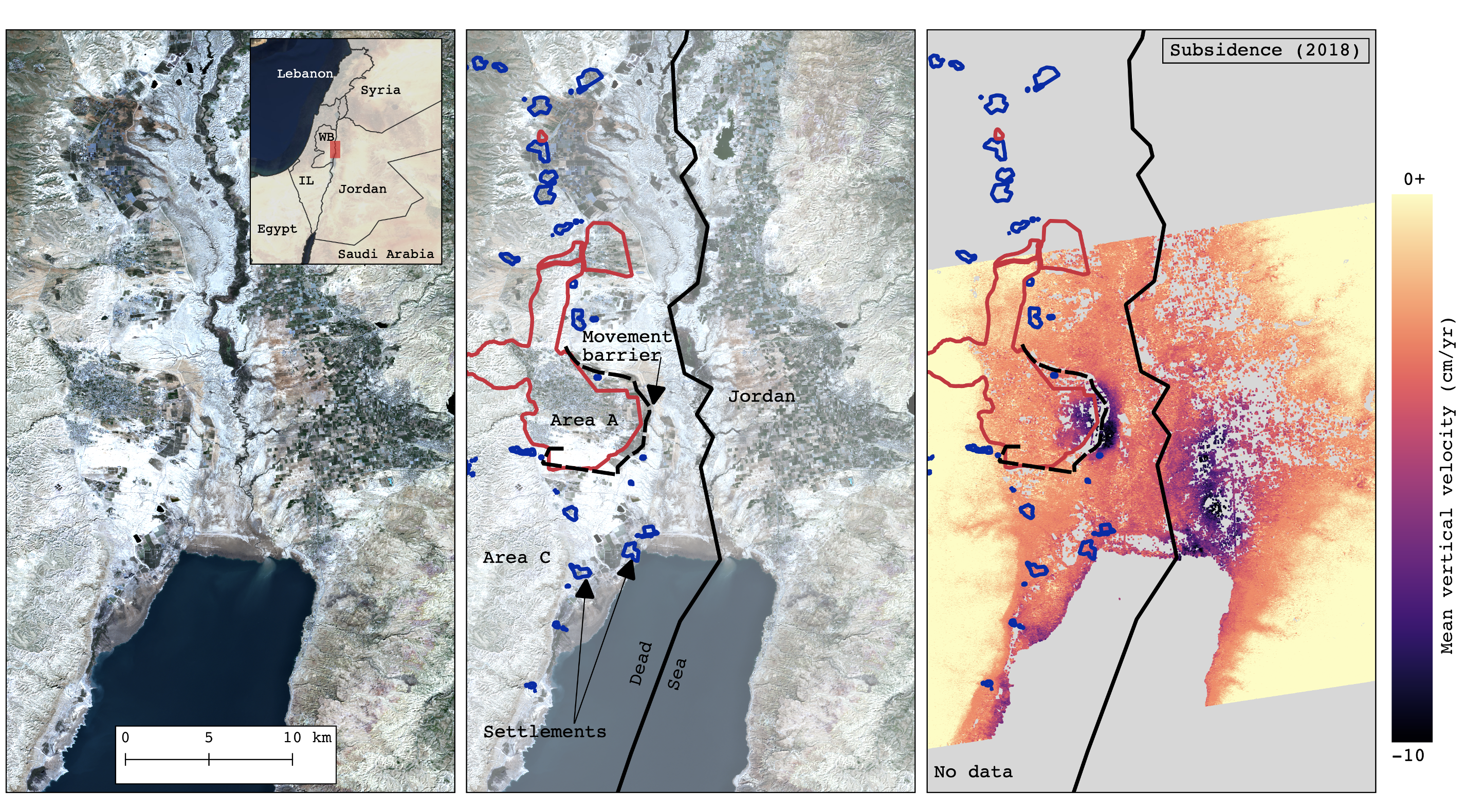

To illustrate the potential value for diplomatic accountability using this technique, I ran subsidence analyses using data from the Sentinel-1 constellation and the Stanford Method for Persistent Scatterers in two transboundary regions with shared aquifers: the US/Mexico border and the southern Jordan River Valley.

I found mean subsidence rates of 5 cm/year near a cluster of pivot-irrigated agricultural fields just on the Mexico side of the border with New Mexico.

There is rapid subsidence on the Jordanian side of the Jordan River Valley, where groundwater level declines of -1.9 m/yr are also the highest rates of any groundwater decline across the entire country. In the West Bank, subsidence seems to mirror the political boundary of Jericho drawn during the Oslo Accords. Agricultural regions around Jericho subside at a rate of around 10 cm/year in 2018.

Data on groundwater level decline on the Palestinian side of the Jordan River are not readily available. Subsidence around Jericho could be driven by Palestinian reliance on groundwater resources from Pleistocene mixed-alluvial aquifers underlaying agricultural regions of date palm cultivation. Interestingly, in regions of date palm cultivation under the control of Israeli settlers, there is little to no subsidence.

In their research on the political role of date palm agriculture in the Jordan River Valley, Julie Trottier, et al, explain that the Israeli Water Authority and Israeli settlers are advancing recycled wastewater infrastructure for agricultural irrigation but Palestinian farmers are not allowed to purchase this treated wastewater; instead relying on pumping from wells. It is possible that Palestinian reliance on groundwater resources is driving the subsidence we see in the eastern regions of Jericho.

In my doctoral dissertation, I argue that subsidence monitoring in transboundary mixed-alluvial aquifers can be used, where applicable, as a physically-based monitor of aquifer condition in pursuit of transparency, accountability, and sustainability of shared water in stressed groundwater resources.